MCSI #034 - The Spectres of Cybersecurity Professionalisation

Professionalisation is haunted by spectres: contradictory evidence, uncertain promises, unresolved concerns, lingering doubts, incomplete solutions, false closure, unseen exclusions, and past scandals.

This essay aims to call out these spectres so they can be examined in themselves but more importantly so that their influence on how we’re approaching professionalisation can be properly examined.

We do not summon the spectres, and even if we choose to ignore them, they still exist.

The Spectre of Racketeering

Someone must pay for professionalisation to be possible – no matter how the fees are presented or who does the presenting.

Here’s published research from legal scholar Rebecca Allensworth that provides empirical evidence from other industries that professionalisation can become a racket: book and podcast.

You can also read her provocative 2013 research paper titled “Cartels by Another Name: Should Licensed Occupations Face Antitrust Scrutiny?”. Here’s a quote from the abstract:

“It can't surprise when licensing boards comprised of competitors exclude competition and regulate in ways that raise their profit. The result for consumers is higher prices and less choice, as licensing raises wages by 18% and bars competition from unlicensed workers. For African-style hair braiders, the result is either an illicit business or thousands of hours of irrelevant training imposed by a cosmetology board. For lawyers, the result is less competition from tax accountants, paralegals and out of state lawyers.

The great accomplishment of the Sherman Act has been to make cartels per se illegal and relatively scarce. Unless the cartel is managed by a professional licensing board. Most jurisdictions consider such boards, as creations of states, to be exempted from antitrust scrutiny by the state action doctrine, leaving would-be competitors and consumers no recourse against their cartel activity.”

Now that you have seen this research, and there’s a lot more of it, the idea that cybersecurity professionalisation could never become a racket on the industry, businesses, or consumers, is no longer certain, no matter how much evidence supports its benefits.

Professionalisation can never fully prove itself “pure” or “just”, as the risk of it becoming a racket is always present. This risk will always be present.

Payment sustains professionalisation yet places it in doubt, creating a cycle of uncertainty. It raises questions about who benefits, whether it delivers value, and if those paying can ever stop.

The Spectre of the Authoritarianism

The rules will be decided by a few for the many, even with industry consultation. And it is all too easy to dismiss inconvenient voices. Hard choices will be made, some ideologies will dominate, and certain voices will be ignored. Some decisions will rely purely on claims of authority – accepted as the "right thing" without proof or concern for opposing views.

Power and authority enable professionalisation but also undermine its credibility. Participants are always left unsure if their interests are valued or if those in power are pursuing another agenda.

The Spectre of Insufficient Control

Imagine a terrible person who commits a serious crime. Their cybersecurity license is revoked, yet they can still write, teach, sell, and profit from the very businesses and consumers professionalisation claims to protect.

Now imagine a small MSP – a two-person company that services micro and small businesses. None of its staff are accredited under the proposed professionalisation scheme. One of their clients requests support to meet Essential Eight Level 1 requirements. Could professionalisation stop the MSP from implementing Airlock, enabling MFA, building an asset inventory, or patching Windows machines? Of course not.

Professionalisation promises protection by controlling who can participate in the market, yet it can never fully deliver – its control is always limited. What and who is being protected then?

The Spectre of Illegitimacy

To prove professionalisation’s legitimacy, supporters point to a 2022 AISA survey showing one in two people in favour. What they overlook is that the survey’s report doesn’t specify the number of respondents, their demographics, or how informed about professionalisation they were. AISA itself chose not to proceed with professionalisation after the survey.

The problem of legitimacy runs deeper than it seems. People may embrace professionalisation today and reject it tomorrow. Legitimacy is never stable – it shifts, stumbles, and resists control.

The push to professionalise cybersecurity in Australia rests on a single, debatable survey. Is that enough to claim legitimacy? Perhaps professionalisation survives not by proving itself, but by insisting we believe in what it cannot prove.

The Spectre of Disbelief

Having a credible group of people run the scheme is critical, yet also impossible because the conditions that establish credibility are always provisional. Credibility can come and go in the blink of an eye. All attempts to assert credibility can be challenged, questioned, or reinterpreted.

Therefore, whoever wins the government’s grant will be trapped in a constant performance, striving to prove their credibility by mimicking the language, structure, and tone of authority to create the illusion of legitimacy. Yet credibility is always haunted by what it denies — the lingering presence of doubt and disbelief.

The Spectre of Endless Regulation

The US DoD’s professionalisation scheme, the DoD Cyber Workforce Framework (DCWF), defines 72 cyber-related roles, with more added every few months. Will it ever stop growing?

With no clear boundaries neatly surrounding cybersecurity, the DCWF includes roles like IT Investment Portfolio Manager, Product Support Manager, Program Manager, Cyber Legal Advisor, Service Designer User Experience (UX), Data Steward, and AI Adoption Specialist.

Professionalisation does not simply expand — it survives by remaining unfinished. Each new role claims to define cybersecurity, yet each addition reveals new gaps that demand yet more definitions. The system sustains itself not by achieving closure, but by taking advantage of the fact that cybersecurity doesn’t have any clear boundaries.

Regulation follows the same pattern. Each rule attempts to impose order, yet every rule creates new uncertainties that call for even more regulation – think of workplace safety standards for example.

Professionalisation does not expand because boundaries are unclear – it expands because no boundary can ever be final.

The Spectre of Insufficiency

Cyber professionalisation pursues ideals like protecting businesses, consumers, and progress itself. Yet these ideals can never be fully reached. When will the public be truly safe? When will progress arrive?

Professionalisation’s desired outcomes are shaped by unreachable ideals – always shifting, arbitrarily defined, never perfectly definable.

How many businesses must be protected for professionalisation to have succeeded? Why this number and not a bigger number? Is success ever knowable at all?

Ideals provide a mechanism for professionalisation to protect itself from scrutiny and accountability: when it benefits the scheme, success can be defined by what has already been achieved. When the scheme needs to justify its continued existence, success can be defined by what still needs to be done.

Professionalisation therefore survives by exploiting ideals. It creates an endless race where participants convince themselves they must keep running. Does that sound familiar?

The Spectre of Exclusion

Which voices are amplified, and which ones are devalued? Professionalisation is an ideology that has winners and losers. It causes a perpetual fear of being on the losing side at some point.

Read my essay about the ideology of professionalisation to learn who and what it devalues. The devaluation works by elevating certain ideas, rewarding conformity, and shaping meaning.

The Spectre of Failure

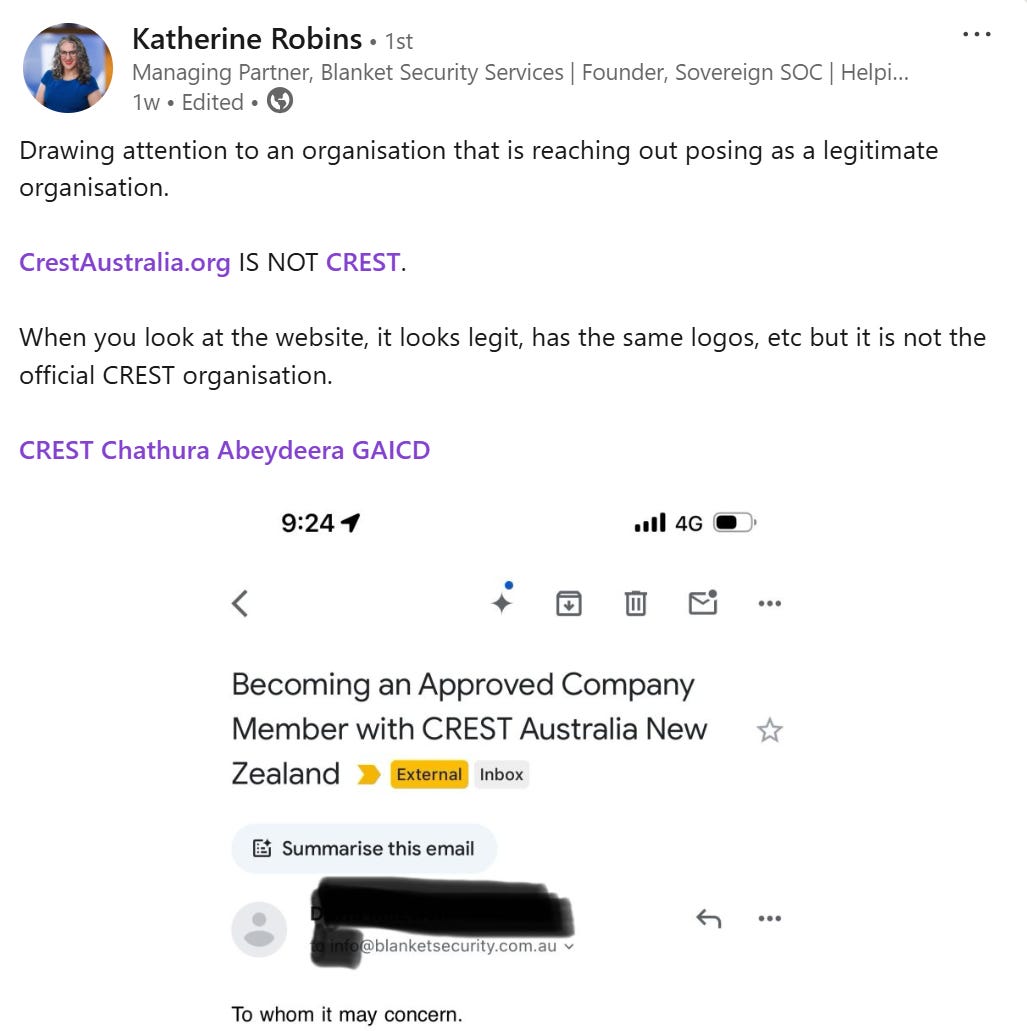

Other cybersecurity professionalisation schemes have failed or fallen short – what will make this one different? For example, CREST ANZ is now considered illegitimate by some:

CREST UK and CREST ANZ are no longer affiliated because of a dispute over the CREST brand and a $10M dollar grant awarded to CREST ANZ under the Australia’s 2016 Cyber Security Strategy:

Any new professionalisation scheme carries the shadow of past failures, scandals, or poor leadership. People may not want it to fail, but the scheme cannot outrun failures from this or other industries, nor put to bed concerns that have arisen from these.

The Spectre of Accountability

Promises of oversight, ethics committees, and whistle-blower policies create the impression that someone can be held to account, yet accountability can never be guaranteed. Therefore, it lingers in doubt, kept alive by the hope that someone, somewhere, might be held responsible – if everything works out. And if accountability does come, to who’s standard?

Each time we inquire about accountability, we reveal its uncertainty. It is a promise that might not be kept. Yet it is also a promise that can have power over us. It controls us by comforting us, at least temporarily, until it fails – and then what?

Conclusion

The spectres cannot be avoided. They haunt everything tied to professionalisation. As a result, for many, professionalisation lives in a place of limbo – they are “unsure” (AISA 2022 Survey).

The deeper we look, the more professionalisation reveals itself as a paradox. It promises control, protection, progress, legitimacy, credibility, inclusion, sufficiency, and accountability, yet it can never fully deliver any of these – neither for itself or nor anyone associated with the industry.

Those who pursue professionalisation would do well to understand the spectres.

Whoever leads the effort to professionalise cybersecurity will be haunted by the spectres. We should empathise with the personal and relational costs they may face in this endeavour.

For the right leaders, the spectres could become an opportunity to listen deeply to the concerns that haunt professionalisation — not to dismiss or control them, that’s impossible, but to create the conditions where people feel safe enough to face those doubts together.