MCSI #033 - The Authoritarian Ideology Overtaking Cybersecurity

The cybersecurity industry is being overtaken by a push for professionalisation. Its proponents justify this push as a necessary step to better protect the public, businesses, and consumers. But a closer look reveals an ideology that elevates certain values, devalues others, and even excludes some values altogether.

What is the cost of this devaluation, and who pays the price? To answer this, we will look to a case study of the UK’s cybersecurity professionalisation scheme, specifically the UK Cyber Security Council Competence & Commitment (UK CSC SPC). We’ll refer to UK CSC as “the Council,” as that’s how its creators describe themselves.

My end goal is to encourage reflection and questioning throughout the industry. By thinking critically about professionalisation, we can reflect on our ethical responsibilities toward those who are devalued or excluded – and decide whether change is necessary.

1) What is professionalisation’s ideal and how is it used for power grabbing?

The first objective of the Council is to “promote high standards of practice in the cyber security profession for the benefit of the public.” (p. 5)

This ideal of protecting the public sets up the entire justification for the Council’s existence. It is repeated in different ways throughout the document, such as on page 7 “Society necessarily places great faith in its cyber security specialists” – implying once more that the society needs cybersecurity professionalisation and, through deduction, the Council.

It’s worth noting that all cybersecurity professionalisation schemes legitimise their existence using a similar ideal. For example, in Australia, AISA talks about “protecting consumers” and Home Affairs about “protecting businesses”.

Whilst the wording might change, the mechanism is the same: an ideal is stated, made absolute, and it becomes the reason for forcing the entire sector into a professional licensing scheme.

But what else might lurk under this ideal aside from good intentions? Before we can answer this question, we must first expose the instruments of power used by professionalisation schemes.

2) How does an ideal impose itself onto an industry?

The Council uses the following mechanisms to operate the scheme:

Registers of cybersecurity professionals

Three titles that establish a hierarchy: associate, principal, and chartered

Licensees that assess and recommend individuals that can be added onto the register

A professional standard, a certification framework, and commitment statements

A Code of Ethics

The Council can take “any action it deems necessary to protect the integrity of the Registers and to ensure that its post-nominal designations are used only by those Registrants entitled to do so” (p. 5).

It is now clear that the document enacts tools of power, but against what or whom?

3) What is valued and devalued under this ideal?

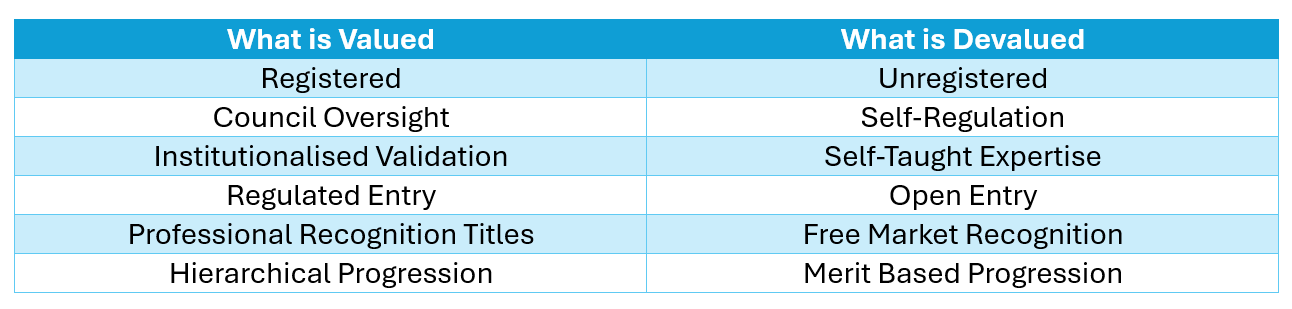

The premise is clear: unprofessionalised cyber professionals are inadequate for society. The Council therefore sets out to professionalise them. This process begins with an ideology of devaluation:

Is this ideology truly stable and absolute? Of course not. We will now examine an example in detail to show how professionalisation cannot exist without the elements it devalues.

4) Institutional Validation above Self-Taught Expertise

The Council has divided cybersecurity into what it calls “specialisms,” such as penetration testing and incident response. But where did the knowledge behind these specialisms come from? It came from individuals who thought of new ideas and taught themselves solutions to solve problems. Only decades later did the Council appear, and declared itself the legitimate authority over who knows this knowledge and what the right pathways are.

For example, the first documented case of antivirus removal was in 1987 by Bernd Fix, who holds a degree in astrophysics. Bernd was involved in computer virus research and even wrote viruses himself, something some might now see as controversial. However, his work played a key role in launching the field of cybersecurity. Reviewing his online CV, I noted that he does not list any cybersecurity certifications despite working in cybersecurity for 39 years.

I did a search for “Bernd” across the Council’s and CyBok’s websites but could not find any reference to his work – even though many of the specialisms were shaped by his contribution (i.e., digital forensics, cyber threat intelligence, incident response and intrusion detection).

Industry innovations come from people like Bernd – those who dare to step outside established ways of thinking. They challenge existing mindsets, ideas, ideals, and ideologies, teaching themselves new approaches to tackle problems that others can’t solve. Should we be devaluating people like that? What opportunities might be missed in doing so?

Proponents of professionalisation claim they do not devalue self-taught approaches – of course! Yet, by promoting an institution that defines who qualifies as a cyber professional, what knowledge matters, and which pathways are valid, they create a system that shapes meaning. This system elevates certain ideas and practices while pushing others aside, ultimately rewarding conformity and limiting what people can do, think, or imagine.

Such an institution forces people to consider whether it approves of their curiosity, creativity, ethics and ideas. What does that do to a person? What will that do the industry?

Unfortunately for the Council, no matter how much authority over knowledge and norms it claims, it remains dependent on the very self-taught people its ideology covertly devalues.

5) Professionalisation or “Profanessionalisation”? Which is more accurate?

No matter the Council’s discourse, it depends on the people and ideas it devalues:

Leaders emerge from merit-based, non-traditional pathways that later become codified

Pioneers start in open environments, later making standards for regulation possible

Self-created norms are first recognized by peers as valuable before being normalised

Competence is first achieved by unregistered experts, only later absorbed into a system

As a play on word, I propose we rename professionalisation to “profanessionalisation” – because it is the profane, the devalued, the excluded, the unregistered and the unlicensed, that enables professional licensing and sustains it via appropriation.

6) What can Australia learn from the UK Cybersecurity Council?

Now that we have shown that professionalisation’s ideology is neither stable nor absolute, that it devalues what it depends on and even excludes those who made it possible in the first place, what should we do?

We must resist the authoritarian pull of ideology itself. We must give voice to those who are devalued because their contributions are essential to professional licensing, society, businesses, consumers and the industry as a whole. We must commit to self-criticism, challenge our norms and question our ways of thinking to prevent absolutist ideals and ideologies from taking hold unchallenged.

Professionalisation seeks to cement a power structure, a hierarchy between professionals, an economic model that benefits some more than others, and even exclude entire categories of industry contributors. Its ultimate victory will be making people think that no alternatives ever existed – or that they were unrealistic, incomplete, maybe even naïve. But was that really the case?

Therefore, we must create ways to encourage behaviours that defy our preconceived ideas of right and wrong. This demands a politics of constant renegotiation with ourselves and with each other. In this way, professionalisation’s true strength becomes its incompleteness. Whereby acknowledging it as a system that always fails makes innovation, ethics and progress possible.

Who will do the honour of challenging the Home Affairs, AISA, and others into a renegotiation?

Original post: https://www.benjamin-mosse.com/professionalisation/2025/03/12/professionalisation-as-the-profane-made-sacred.html